Recent research from Penn Medicine and Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia highlighted a troubling truth: Exposure to gun violence trauma is associated with higher rates of mental health-related emergency department visits by children.

In the study, a child is considered exposed to gun violence when they live within 4-5 blocks of a shooting reported within 60 days, causing mental health concerns including PTSD, depression, and intentional ingestion of harmful substances.

This study underscores the need for more robust gun violence trauma intervention efforts, especially in urban communities. To understand what this can and should look like, let’s first understand the deeply rooted problem and the impact of gun violence on communities.

What is Gun Violence Trauma?

Trauma, generally speaking, is an emotional response to a distressing situation.

Gun violence, including just the sound of gunfire alone, is a distressing experience to most people, especially to those not accustomed to hearing it—or are too young to process what it means.

The prefrontal cortex, which is part of the brain that impacts emotions, is not fully developed until about 25 years old. This means gun violence trauma has lasting and actual biological impacts on children who are not yet fully developed. When exposed to higher levels of toxic stress, there is often a real, chemical change in the brain.

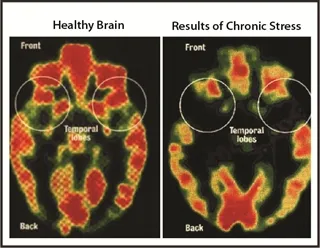

In fact, cognitively, the brain develops differently when exposed to higher levels of trauma. Just look at the two brains below: a healthy brain versus one exposed to long periods of trauma. The traumatized brain is smaller, and the neural pathways that help the individual make complex decisions are altered.

Source: Illumination Foundation

The problem magnifies when you consider other adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) a child may experience beyond gun violence. Living in poverty without access to an adequate amount of healthy and nutritious food, clean water or safe shelter is an ACE—and living in poverty in an urban environment exposed to toxins creates even more ACEs. Add in gun violence and you get a poly-traumatic experience, which impacts a lot of different cognitive and physical development.

Here’s how this cognitive change impacts children in the short term and long term.

Short-Term Impacts of Trauma

Even though kids may be exposed to war-like violence every single day, they are still expected to go to school. Trauma shapes their perceptions of how they respond to future trauma, which typically leads to two reactions when it comes to school:

- Skip, or be frequently tardy to school out of fear and avoidance of further trauma.

- Normalize gunfire in order to cope with it and become hypervigilant negatively affecting behavior in school and educational attainment.

When a child’s brain is altered and maldeveloped due to trauma, they may take something as a threat that most people wouldn’t see as a threat and become hypervigilant, defensive, and aggressive as a response. Further, when this trauma is normalized, it can increase the likelihood of the development of self-destructive or reckless behaviors, create problems with concentration, and increase anger outbursts in the classroom.

Ultimately, students are less likely to go to school and more likely to carry weapons of their own. Hypervigilance, anti-social behavior, and outbursts—as well as truancy—cause more problems as the child moves into adolescence. They are more likely to be suspended and not graduate. Carrying a weapon due to hypervigilance will negatively impact interactions with other people and police and makes it more likely for the student to become involved with gun violence and end up in the criminal justice system.

Long-Term Impacts of Trauma

Moving into adulthood, those with ACEs and high levels of long-term toxic stress are more likely to be involved in intimate partner violence. They are more at risk to overreact to something with those they are closest to.

It’s evident that gun violence trauma combined with other ACEs has a lasting and significant impact on our nation’s communities. What steps can we take to break the cycle of gunfire and get communities the support they need?

Gun Violence Trauma Intervention

The first key to intervening with gun violence trauma is to stop the traumatizing factor in the first place.

This leads us to a pressing problem: Gunfire isn’t being reported.

In the U.S., upwards of a whopping 88 percent of gunshot incidents are never reported to the police. If gunfire isn’t being reported, police can’t identify where it’s happening and they can’t help. This is critical information because, as stated, a child is considered exposed to gun violence when they live within 4-5 blocks of a shooting reported within 60 days. Gone unreported, this trauma—and resulting mental health and cognitive development concerns—continues to take its toll.

The quicker a community gets resources to stabilize these traumatized children, the better. The longer you wait, the more likely it becomes a maladaptive behavior norm, and the cycle continues.

Today, technology is critical to intervening with gun violence trauma. It can let the police know where gunfire is happening, within those 4-5 blocks, so they can in turn partner with community organizations and other government agencies to give traumatized individuals the resources they need to heal and thrive.

Here’s what this looks like.

#1. Identify Gunfire Incidents

If we don’t help law enforcement identify gunfire incidents and investigate shooters, then we won’t be able to lessen the likelihood of continued trauma. So, the most immediate step is to stop the triggers to the trauma, which is continuous gunfire.

Gunshot detection technology helps determine where gunfire is happening in real time. It also gives historical data, heat maps, and trend analysis of where it’s happening the most.

With this information at hand, cities and governments can identify where they should send mental health and other community stabilization resources.

#2. Provide Services to Communities

Having the data is one thing. What communities and governments do with that data next is vitally important.

High concentrations of gunfire inform where trauma is occurring. This data should be shared with organizations that can provide resources to the community. For example:

- The Office of Violence Prevention Network

- Churches and other faith-based organizations

- Community Development Financial Institutions

- Federally Qualified Health Centers

- Workforce Development and Training Organizations

The key is extending this gunfire data from law enforcement to other organizations that can provide additional resources that seek to provide protective factors against future gun violence. Partnering with these agencies both address the current traumatic impacts of gun violence as well as provides protective factors against future gun violence, by helping to implement a public health approach to violence prevention. In this approach, the non-law enforcement interventions are just as important as law enforcement intervention; in fact, the two must work together in order to fully address the cycle of gun violence.

Conclusion

Gun violence trauma is just one of many traumatic experiences that communities experience, in addition to basic needs like food, water, and shelter. Gunfire on top of other challenges is extremely impactful. But with the right data at hand, it is one with a clearer intervention roadmap.

While police focus on identifying, responding to, and investigating crime, these other organizations can focus on identifying, responding to, and intervening with gun violence trauma and addressing other root causes of violence in a parallel path.

SoundThinking™ is committed to using our data to positively serve our nation’s communities. To learn more about our gunshot detection technology and how we can partner to provide communities the resources they need to intervene, contact us here.